The last battle order issued by Canadian General Guy Simonds to the 1st Polish Armoured Division under General Stanisław Maczek was to occupy the German port in Wilhelmshaven, the main base of the German navy.[1] The Polish 1st Armoured Division was included within the 2nd Canadian Corps commanded by General Guy Simonds. Canadian and Polish soldiers had fought side-by-side all the way from the beaches of Normandy all the way to Germany.

In action to the end, the Polish artillery pounded German positions until one minute before the ‘cease fire’ on the morning of May 1”[2] Poles let go a final artillery barrage as an honorary salvo to end the war. On May 5, 1945 the 1st Polish Armoured Division accepted the surrender of the Kriegsmarine naval base in Wilhelmshaven, where Col. Antoni Grudziński on behalf of General Maczek accepted the capitulation of the fortress, naval base, East Frisian Fleet and more than 10 infantry divisions. On May 8, 1945 Germany formally surrendered. The World War II has finally finished in Europe.

It was in this corner of Germany that the Division ended the war and, joined by the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, undertook occupation duties until it was disbanded in 1947. Together with the many Polish displaced persons in the Western occupied territories, these two units formed a Polish enclave at Haren in Germany, which was for a while known as “Maczków”. The majority of its soldiers opted not to return to Poland, which fell under Soviet occupation, preferring instead to remain in exile. Where would they choose to go now? Who would have them?

It would be natural for these Polish soldiers who fought alongside Canadians, as brothers-in-arms, would think that Canada would welcome them and that Canada would make a great future home. Well, not as welcoming as one might think. In 1945-1946, the Canadian government was reluctant to absorb Polish Veterans and refugees that were stranded in Europe after World War II. The International Refugee Organization and the British government began to pressure the Canadian government into accepting more of these people. Canada set up a Senate Committee on Immigration to consider the desirability of admitting more refugees, and at this time the Polish soldiers were simply regarded as refugees. In July 23, 1946, after considerable negotiations, Canada allowed for 4000 Polish veterans to come to Canada as farm labourers. These veterans would have to agree to work on Canadian farms for two years, under less-than-ideal conditions. Most of these first veterans came from the Polish 2nd Corps, since the veterans of the 1st Polish Armoured Division were engaged in work in occupied Germany. As a result, the veterans of the 1st Armoured managed to avoid the humiliation of farm work, with many of these veterans isolated from one another in small towns across Canada.

In July 1947, the Canadian Senate Committee on Immigration submitted a report advocating for a substantial increase in immigration. The Canadian Government adopted a more open immigration policy and between 1947-1951, and 36,549 displaced Poles entered Canada, including many of those who had served with the 1st Polish Armoured Division. At the same time, the Polish Combatants’ Association of Canada had already been established, again largely by veterans of the Polish 2nd Corps, so by the time the veterans of the 1st Polish Armoured Division arrived, they were able to avoid farm labour, were welcomed by an already established Polish veterans’ association, and were not sent to isolated small towns across Canada.

As a result, most of the veterans of the 1st Polish Armoured Division, could choose to settle in larger Canadian cities, especially those with established Polish communities, such as Toronto and other cities in Ontario. They came as immigrants to a new country following established immigration criteria. This is not to say that these veterans did not encounter any problems in transitioning to life in Canada, but it is clear that some of the more difficult ground work had been done before their arrival.

In general, the veterans of the 1st Polish Armoured Division, were somewhat older than the veterans of the 2nd Polish Corps, had higher education levels, and had access to greater training opportunities, when the division was being formed in Scotland and after the war when they were given the opportunities to further their education in Great Britain.

As a result, the records of the lives of the veterans of the 1st Polish Armoured Division, who settled in Canada, often show them taking on professional careers or establishing their own businesses. A cursory look at some of their chosen careers identify positions in international trade, engineering and finances. Some became entrepreneurs and had their own plumbing and entertainment businesses. Some opened restaurants. Some took on leadership roles both in Canadian society and in Polonia. And, of course, some had well-paying factory jobs.

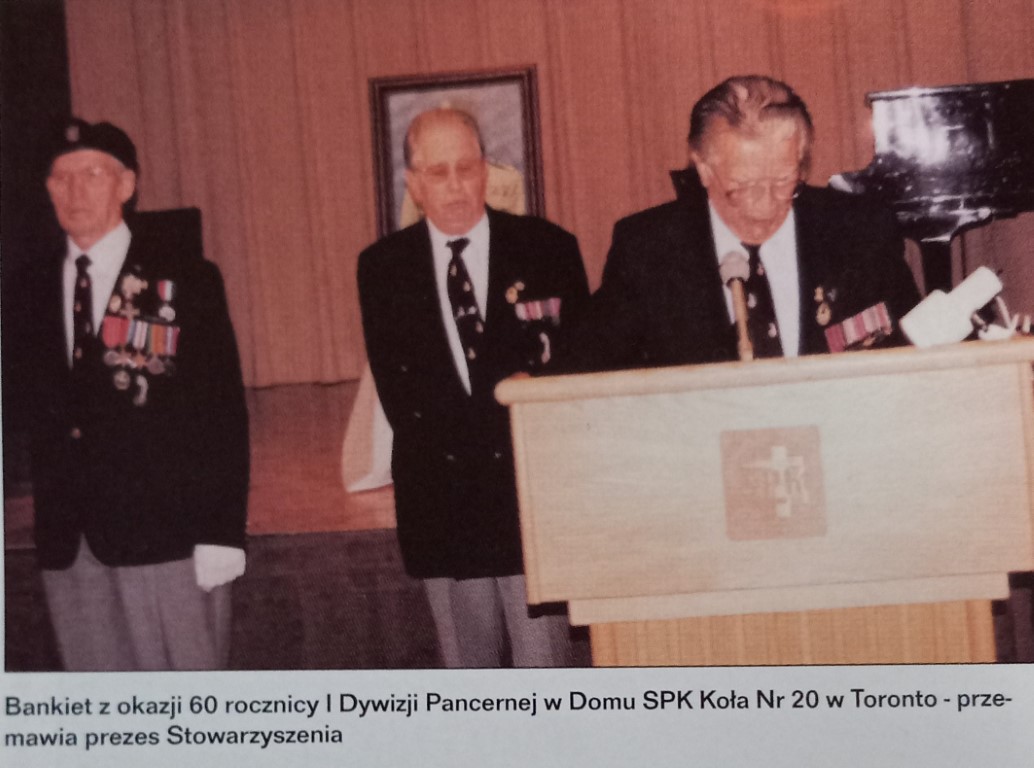

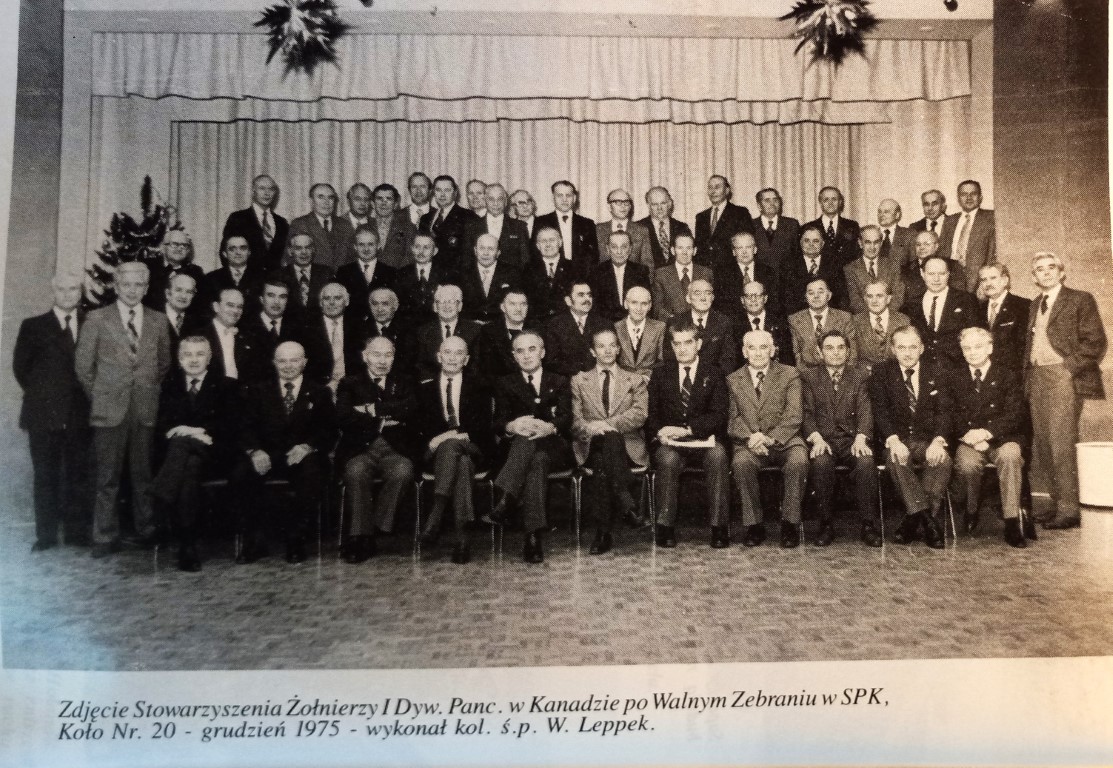

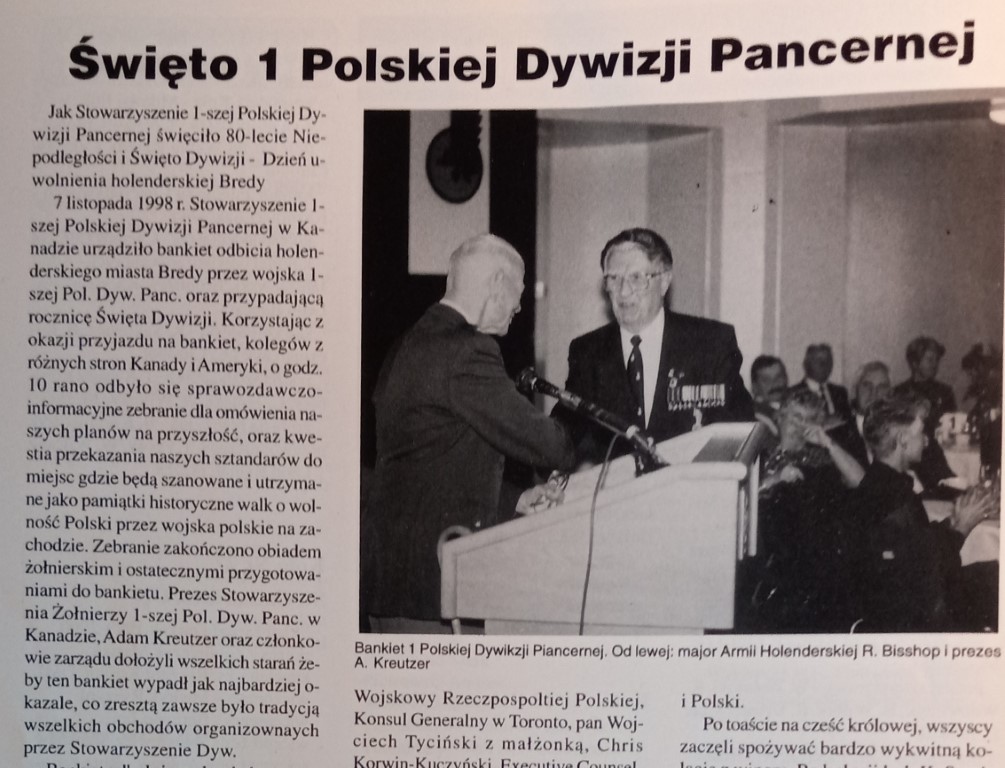

The veterans tended to be very active in the many branches of the Polish Combatants’ Association, often taking on leadership roles. They also established their own association – The First Polish Armoured Division Association in Canada, which at their peak had over one hundred members and was very active in the Polish community in Canada.

Today, all the veterans of the 1st Polish Armoured Division who settled in Canada are dead. No veterans remain. But the echoes of their work and monuments and memories to their contributions both during the war and their lives in Canada remain. They will be remembered. Cześć Ich pamięci!

author: Stan Skrzeszewski, Canada

[1] Stanislaw Maczek, Od podwody do czolga: wspomnienia wojenne 1918-1945. (Ossolineum, 1990), p. 207.

[2] Charles P. Stacey, Six Years of War, Volume 3, The Victory Campaign (598)